In 2003, in the essay “Delirious No More,” Rem Koolhaas cast the planned rebuilding of the World Trade Center as a death knell for the feverish experimentalism he had so enthusiastically chronicled 25 years earlier in Delirious New York.

In the gargantuan scale and literal symbolism of Daniel Libeskind’s competition-winning rebuilding scheme—in essence, voids on the sites of the old towers and a perimeter of new towers culminating at 1,776 feet—monumentalization took the place of imagination. Vast sums of public money bought a decades-long series of ribbon-cuttings, and commerce made its return—not organically, as a new beginning for the site, but opportunistically, in the form of a high-end mall and kiosks around the memorial that peddle official 9/11 Museum–themed merchandise. Even as Lower Manhattan, far from being deserted, grew into a lively residential area, Ground Zero remained an artificial zone of granite and marble. “New York,” Koolhaas had warned, “will be marked by a massive representation of hurt that projects only the overbearing self-pity of the powerful.”

The 138-foot-tall translucent marble cube of the Perelman Performing Arts Center is the latest monument on these 16 acres of Lower Manhattan. Rising directly opposite the 9/11 Memorial and adjacent to the impregnable base of SOM’s One World Trade Center, the 129,000-square-foot building was designed by REX with Davis Brody Bond as the final civic project for Ground Zero under Libeskind’s master plan (one commercial tower and one residential tower have yet to be built). As such, it offers a modicum of closure even as it trumpets the achievements of those responsible for guiding the rebuilding over the past two decades. Inside and out, the walls of the $500 million building are inscribed with their names: the developer Larry Silverstein, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, Citi, Goldman Sachs, former deputy mayor John E. Zuccotti, and, of course, Ronald Perelman, the businessman who kickstarted the project with a $75 million gift in 2016.

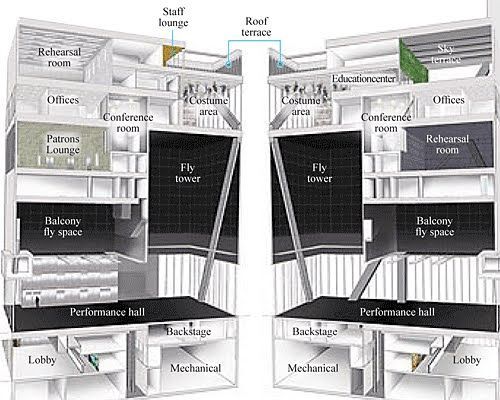

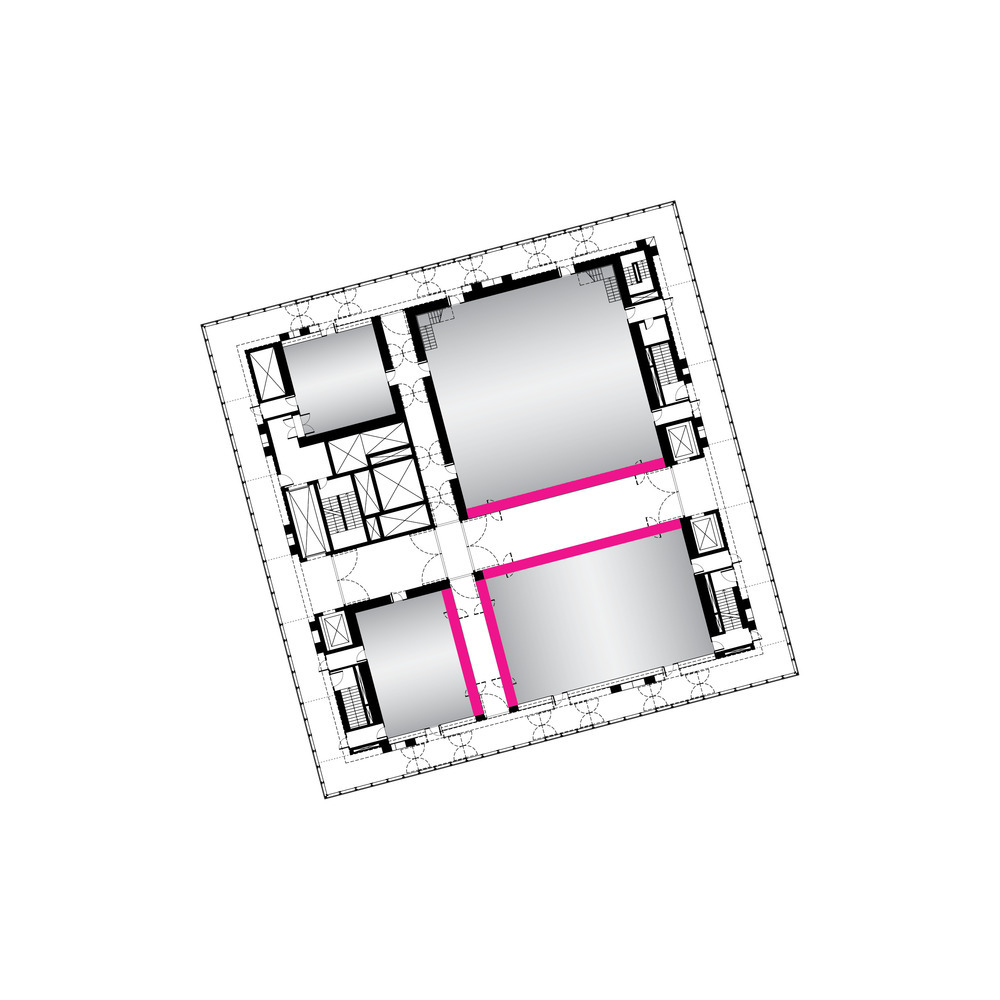

But if the Perelman Center is in this sense par for the Ground Zero course, hidden within its mute walls is an attempt to challenge architectural convention of the sort that has until now been absent from the site. The building is conceived around three performance venues, located on the fourth floor, which can be separated or combined in 10 spatial permutations. Movable floors, seating, balconies, and other equipment then allow each permutation to be further customized; in total, according to REX principal Joshua Ramus, there are more than 60 possible configurations, catering to performances of all kinds. (The center’s inaugural season encompasses multiple varieties of theater, music, and dance, among other events.) This highly scripted mode of flexibility is distinct from that of black-box theaters, which begin as empty spaces: “strategic specificity,” Ramus says, “can prove to be more flexible than universal space.”

From an ingenious system of lifts beneath the floors that each fold down into an impossibly small steel drum, to four mechanized guillotine walls, to movable panels near the ceilings that allow each space to be acoustically optimized for a given configuration, the building is filled with machinery designed to ease the implementation of this flexibility. Acoustics, code compliance, circulation needs, and access to the scene elevator and back-of-house, among other factors, have all been considered across each configuration, enabling artists to experiment freely with the building. “The design encourages play,” says Bill Rauch, Perelman’s artistic director.

Creating so complex a machine at Ground Zero was no easy feat. The Perelman Center sits on four levels of underground infrastructure—two rail tunnels, a pedestrian concourse, and a vehicular ramp; and its ground floor, clad in black granite, is dedicated to Port Authority infrastructure, including a truck entrance that provides access to underground loading docks across the World Trade Center site. Further complicating matters, much of the underground infrastructure was designed and built years ago, when planning for a performing arts center had yet to progress beyond an initial scheme by Frank Gehry. Gehry’s design, which was abandoned in 2014, had fixed the location of the scene elevator, used for bringing large set pieces from the loading dock to the theaters—and so, when REX was hired in 2015, the architects had to design around the elevator while working with structural engineers to identify points for the building’s columns to tie into the below-grade structure. They found only seven such points, and, as a result, the building had to be as light as possible—even its egress stairs(비상계단) are enclosed in plate steel rather than concrete—and its steel columns had to “play a game of Twister,” as Ramus puts it, as they snake their way up and culminate in an enormous hat truss around the perimeter of the upper floors. Enclosed within that truss are the three venues, each of which is a self-supporting structure resting on rubber pads that isolate it from vibrations.

Stairways and elevators then take visitors up, past the back-of-house spaces on the third floor, to the theaters above. There they find themselves in a set of dark circulatory spaces that can be freely reconfigured so as to shift the boundary between front and back of house; another orange-hued perimeter hall, this one triple height, provides access to the three venues, configured in plan in a large L, and a rehearsal room. The venues, which in their most basic configurations seat 99, 250, and 450 patrons, respectively, are surprisingly small and straightforward. The only adornment of note is wood paneling, cut into a variety of vertically oriented molding-like profiles for optimal acoustic diffusion, which lines the walls of all three rooms.

The Perelman Center is not the first theater project to pursue architectural mutability, nor is it the first to posit a link between ultraflexible architecture and radical or innovative art. The same theme animates the Dee and Charles Wyly Theater in Dallas, designed by Ramus as partner in charge of the project at REX/OMA and Koolhaas. Earlier Koolhaas projects had explored this theme in different ways—in the oversize doors that link the expo hall, conference center, and concert venue at the Congrexpo near the Lille international rail depot (1994), for example, and the segmented movable floor proposed for the unbuilt Ghent Forum (2004). And another architect of similar inclination, Elizabeth Diller of Diller Scofidio+Renfro, led the design of the Shed at Hudson Yards in Midtown Manhattan, where an enormous ETFE-clad sheath literally rolls out over an adjacent plaza on 6-foot-diameter wheels.

Beyond the shared commitment to mutability, the Perelman Center and Shed have much in common. Both are conceived as “cultural” components of master-planned Manhattan megadevelopments. Both consist of newly formed institutions dedicated to producing interdisciplinary arts programming married to luxe, purpose-built buildings. And both have been enabled by the largesse of Manhattan’s rich and powerful. The two even share a primary benefactor, Michael Bloomberg, whose gifts have totaled around $130 million to each.

Both also raise similar questions about the limits of mutability as an architectural concept. To what degree are these elaborate mechanisms employed not for practical ends but rather for the purposes of attracting media attention and philanthropic support? Arts organizations have an easier time raising money for capital projects than operations, and one might argue that, by making mutability part of the architecture of the Perelman Center, REX has reduced pressure on future operating budgets. But, ultimately, how necessary, and how useful, are its 60-some configurations?

Many of the architects who in the past championed mutability did so in order to mount critiques of elite institutions. Cedric Price’s unbuilt proposal for the Fun Palace, created with the theater producer Joan Littlewood in the early 1960s, consisted of an enormous, endlessly reconfigurable structure where people of all walks of life would be welcomed to participate in performing and creating art. And the ambition that underlies many of OMA’s ultraflexible performing arts projects, such as the Taipei Performing Arts Center, has been to refigure the relationship between performance and public: to liberate theater, opera, and other forms of performance from the architectural conventions that keep them sequestered in a rarefied cultural realm. Ramus’s own soon-to-debut Lindemann Performing Arts Center at Brown University, where a glazed horizontal volume cuts through the main theater, enabling passersby to glimpse performances from the surrounding streets, takes its place within this lineage.

The Perelman Center, by contrast, and due in large part to its marble facade, takes on no such project. The envelope is doubtless a technical feat: its insulated panels, each fronted with a ½-inch piece of Portuguese marble sandwiched between two pieces of glass and each weighing almost 300 pounds, necessitated a production chain spanning four countries. Book-matching the nearly 5,000 panels, and then fitting them into symmetrical patterns on four largely identical facades, required an extraordinary degree of coordination on the part of REX’s staff and consultants.

Ramus argues that the building’s stark simplicity and the luminosity of its facade—at night, it glows an even amber—will create a sense of mystery and draw in the public. But the facade is also a tool that keeps what happens inside the center invisible, and this is no accident: it was a preference of the client during the initial competition, Ramus recalls, that activity within the building not be visible from the 9/11 Memorial. And a critical element of REX’s design that would have at least suggested a link between performance and the outside world—glass walls facing the marble facade on the third floor, within the back-of-house spaces, and in two of the theaters and the rehearsal room on the fourth—was cut. One consequence of this change is that the drama of the facade cannot often be appreciated from indoors; one’s awareness of the outside world disappears all too easily. Another is that the single floor dedicated to staff and performers is entirely without natural light.

At the Perelman Center, the timeworn pattern of Modern architecture repeats itself: a formal technique conceived to effect social change is subsequently repurposed to perpetuate the status quo. Here the inflated social status of the performing arts is reasserted rather than challenged. Perhaps this conclusion was preordained: one suspects that the powers that have controlled the Ground Zero rebuilding would have had it no other way. Nonetheless, entombed within these marble walls, the impulse to use architecture to enable the creation of new forms of art, to change how spaces are occupied, to reconfigure the city—the original promise of the rebuilding—can still be detected. It is the ghost in the strange machine that is the Perelman Center—a quiet reminder of how things might have turned out differently.

'03 잡학 스크랩' 카테고리의 다른 글

| ParkLife. Austin Maynard Architects (1) | 2023.10.30 |

|---|---|

| John Morden Center. Mae (0) | 2023.10.30 |

| [스크랩] U2 The Sphere (0) | 2023.10.24 |

| [스크랩] Microsoft 365 Copilot (0) | 2023.10.24 |

| [스크랩] How “dementia villages” work (0) | 2023.05.16 |